Narrative, creative – immersive? The immersive potential of right-wing extremist communication on social media

| Sandra Kero Center for Advanced Internet Studies (CAIS), Bochum | Josephine B. Schmitt Center for Advanced Internet Studies (CAIS), Bochum |

Social media is ubiquitous. More and more people are using platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to share their experiences, opinions and interests directly with others. But what does this mean for our experiences in these digital spaces – and what effects does it have on the formation of our political opinions? In particular, the immersive experiences that users have in these media environments can trigger powerful emotional effects and influence political or ideological attitudes. In this blog article, we look at these immersive effects of social media platforms. Alongside a detailed examination of what exactly immersiveness can mean in this context, we present mechanisms that contribute to the immersiveness of right-wing communication on social media, taking into account concepts and theories from media science, communication science and psychology. Based on these findings, we then provide recommendations for action aimed at developing preventive and repressive measures to counter the improper and antidemocratic use of immersive environments.

INTRODUCTION

Social media platforms like Instagram or TikTok are a popular tool of right-wing actors. As political outsiders, they exploit the opportunities that social media offers to establish them-selves as independent voices outside journalistic media for the purpose of orchestrating their narratives, channelling their political opinions and ideological attitudes and recruiting new members (Fielitz & Marcks, 2020; Rau et al., 2022; Schmitt, Harles, et al., 2020; Schwarz, 2020). On Instagram, right-wing groups deliberately rely on creators, lifestyle and a connection to nature to make their ideology more easily digestible (Echtermann et al., 2020). As a result, ideological content is not only subtly presented – often, the corresponding ideological perspectives are explicitly stated (Kero, in press). But also TikTok, which is particularly popu-lar among young users (mpfs, 2022), is becoming increasingly important as a platform for the far-right to interact with target groups that have not yet formed firm political views (pre:bunk, 2023). The range of content provided is broad here too: alongside supposedly humorous and musical content, there is also material from AfD politicians who showcase their beliefs. Extreme right-wing ideas are made accessible through normalisation strategies, e.g. pseudo-scientific misinformation and emotionalisation (Müller, 2022).

Social media platforms not only give everyone the opportunity to enter the public political discourse – the disseminated content also allows boundaries between political information, entertainment and social issues to become blurred. At the same time, various functions of social media facilitate users’ immersive experiences – something that far-right extremists in particular can benefit from in their communication practices.

This article aims to contextualise the immersiveness of extreme right-wing content on social media and present selected immersive mechanisms within these environments as examples. On the basis of this, preventive measures are identified.

WHAT DO WE UNDERSTAND BY IMMERSION?

Immersion essentially means being deeply absorbed or engrossed in a particular environment, activity or experience (Murray, 1998). Immersion is often mentioned as a feature of digital technologies such as virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR), or in the gaming industry (Mühlhoff & Schütz, 2019; Nilsson et al., 2016). From a media theory and media psychology perspective, the term primarily describes the state of dissolution of physical and fictitious boundaries, i.e. users’ subjective experiences of plunging into an imaginary world or narrative environment and being emotionally involved in it (e.g. E. Brown & Cairns, 2004; Haywood & Cairns, 2006). This is usually associated with a strong feeling of presence in which perception and attention are focused on the specific immersive content. Conversely, attention to time and (real) space decreases for the period of immersion (Cairns et al., 2014; Curran, 2018). Immersive environments and mechanisms can encourage engagement and learning (Dede, 2009), but can also promote the ideological effect of content among users (Braddock & Dillard, 2016).

Moving away from an understanding of the term that is limited to a technically or culturally versed or psychological phenomenon, Mühlhoff and Schütz (2019) consider immersion from an affect theory and social theory perspective. Here, immersion is described as a dynamic interaction between (non-)human individuals and between them and their environment, i.e. as “a specific mode of emotional and affective involvement in a current or mediatised social event” (p. 20). Affects are spontaneous, instinctive reactions that can be influenced both individually and socially and which shape a person’s behaviour (Strick, 2021, among others). The design of certain (media) environments can influence affective reactions in specific ways and thus also modulate power relations and social dynamics (Mühlhoff & Schütz, 2019). In this sense, certain immersion offerings can help to control and regulate behaviour, thus creating “immersive power” (p. 30). Immersion can therefore be considered a form of situational in-fluence exerted on the thoughts and feelings of the individual. It represents an indirect exercise of power that arises without hierarchies and through social contexts.

Immersion is considered in a wide range of scientific disciplines (e.g. psychology, computer science, cognitive science, design); therefore, the synonyms and closely related concepts are just as diverse. The literature thus includes terms such as presence, flow, involvement and engagement, which describe similar phenomena (e.g. Curran, 2018; Nilsson et al., 2016). To describe psychological immersion in the context of the reception of narrative media content, the term transportation is used in media psychology and communication science research (e.g. Moyer-Gusé, 2008). Immersion as a subjective experience of users is not limited to a specific medium or technology. Learning situations, books, films and social media content can therefore also have an immersive effect, as well as computer games or VR applications.

Against the backdrop of this integrated understanding of the term, we focus in this article on immersive mechanisms in and through social media and their content. We are therefore primarily concerned with the social and psychological dimension of immersiveness.

IMMERSIVE MECHANISMS IN SOCIAL MEDIA

Social media can contribute to immersive mechanisms and effects in various ways. With an understanding of immersion from a media theory and media psychology perspective, these experiences relate to the constant presence of smartphones and, with them, social media applications in our everyday lives, resulting in a merging of virtual, physical and social space. Users’ emotional involvement is also intensified through the primary type of use of social media platforms – such as direct sharing of everyday experiences, interests and opinions – and the (psychological) connection with individual producers of this content, hereinafter referred to as creators, and their posts. From a social theory perspective, a power structure is created here in which affective dynamics can be used in a targeted way to influence the behaviour, attitudes and perceptions of individuals.

In the following, we aim to take a closer look at the underlying mechanisms in order to thoroughly examine the immersive potential of social media in the communication of extreme right-wing creators. A distinction is made between two contexts: the platform environment as an environment of social events, and the interaction between individuals and content in this environment.

Presenting the persona and the story

In the competition for the undivided attention of users, diverse far-right extremists are also taking to social media. The amount of extreme right-wing content has been steadily increasing for years (e.g. Munger & Phillips, 2022). Opinions are becoming things that can be sold. Social media marketing strategies are being used to attract and retain the attention of users (Cotter, 2019) and shape opinions in line with right-wing ideology. How the particular media persona is presented and the way in which the stories are told play a crucial role when it comes to the immersiveness and impact of the content provided.

A number of creators and influencers have emerged from the far-right scene in recent years. They are an essential prerequisite for reaching users, especially those who are otherwise not interested in political content. Generally speaking, influencers are previously unknown social media users who become well-known personalities through careful self-promotion and regular posting of content on social media, and who cover a range of topics on their channels (Bauer, 2016).

Female activists in particular use popular social media platforms to present extreme right-wing ideology to a wide audience in a personal and emotive way through recipes, beauty tips and inspiring landscape photos (Ayyadi, 2021; Echtermann et al., 2020; Kero, in press); the boundaries between entertainment, lifestyle and politics are fluid. The creators act as role models (Zimmermann et al., 2022), are opinion leaders as regards content that threatens democracy (Harff et al., 2022), can attract users to content and channels, and encourage interaction via personal connections (Leite et al., 2022). The greater the trustworthiness and centrality of the creators, the more the recipients report immersive experiences with the media offering (Jung & Im, 2021).

| Figure 1: TikTok channel “victoria” – a mix of nature, homeland and historical scenes | Figure 2: The youth organisation of the AfD – classified as an extremist group that threatens the constitution – posts satirical clips on TikTok |

Above all, it is the communicative presentation styles of the content producers that let recipients really immerse themselves in their everyday world. They tell stories of nature, homeland and a sovereign German people, and provide simple answers to complex political questions. Concepts of enemies as those responsible for social problems are soon found and quickly identified based on supposedly distinct characteristics (see Figure 1). Through their narratives, they not only engage to create identity and meaning, but also offer recipients a strong group that provides interested individuals with a framework and (political) orientation. Formats with an emphasis on humour, pop culture and youth culture are used to make content easy to digest and build recipients’ loyalty to channels and creators (Schmitt, Harles, et al., 2020, see also Figure 2). The network of right-wing actors on social media is dense; they refer to each others’ stories and narratives – including across platforms (Chadwick & Stanyer, 2022). An apparent consistency of narratives, i.e. the same story is told by several actors, makes a story appear even more credible.

MECHANISMS OF NARRATIVE PERSUASION ARE USED FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES

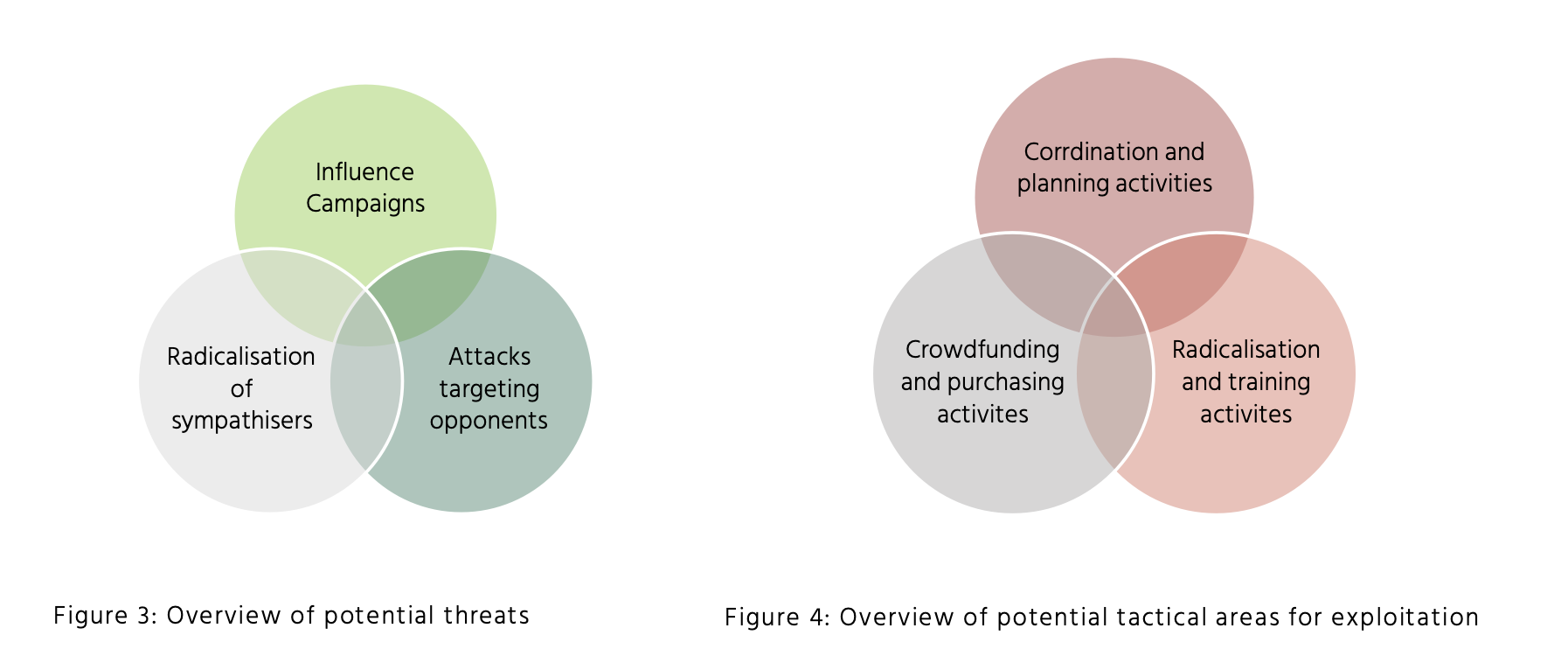

Research in the fields of media psychology and communication science identifies three mechanisms that make stories convincing and thus make right-wing extremist communication particularly immersive and effective: transportation, identification and parasocial interactions (e.g. Braddock, 2020).

Transportation describes the process whereby, in order to understand the narrative presented in a story, people must shift their attention from the real world around them to the world constructed in the narrative. Ideally, as a result of this psychological immersion, they lose their awareness of the real world and completely immerse themselves in the fictional world (Braddock, 2020). More engagement with the narrative world means less questioning of persuasive information (Igartua & Cachón-Ramón, 2023; Moyer-Gusé, 2008).

Identification means the adoption of the media character’s viewpoint or perspective by recipients. This happens, for example, where the media figure is perceived as being particularly similar.

Parasocial interaction is a psychological process in which media users like and/or trust a media figure so much that they feel as if they are connected to them. Where this happens over a longer period, e.g. several videos or articles, it is also called a parasocial relationship. A parasocial interaction or relationship with a media figure reduces users’ reactance to the content presented and the desire to object to content. This facilitates the adoption of beliefs, attitudes and behaviours (Braddock, 2020).

Through narrative storytelling, the direct presentation of everyday situations, self-disclosure and directly addressing recipients, right-wing creators can increase the level of their authenticity and reinforce parasocial relationships with their followers. The more socially attractive a media figure is perceived to be (Masuda et al., 2022) and the greater the recipients’ identification with the media figure (Eyal & Dailey, 2012), the stronger the parasocial relationship. Social media creators offer young users in particular great potential for identification by presenting themselves as similar to them and approachable (Farivar & Wang, 2022; Schouten et al., 2020). An example of this is the account belonging to Freya Rosi, a young, right-wing creator. With tips on beauty, baking and cooking and photos of nature, she orchestrates the image of an approachable, traditional young far-right supporter who loves her homeland (a detailed analysis of the account is also found in Rösch, 2023). A particularly close and enduring parasocial relationship with social media protagonists can even lead to addiction-like behaviours among users (de Bérail et al., 2019). In other words: users have difficulty escaping the fictional world manufactured by the social media creators – in this context their content has a highly immersive effect.

| Figure 3: Screenshots of Freya Rosi’s Instagram account. With tips on beauty, baking and cooking and photos of nature, the creator orchestrates the image of an approachable, traditional young far-right supporter who loves her homeland. A detailed analysis of the presentation strategies can also be found in Rösch, 2023 | |

Self-disclosure by creators can lead to a higher level of parasocial interactions and relationships among followers via the feeling of social presence, i.e. perceiving the media figure as a natural person (Kim et al., 2019; Kim & Song, 2016), and to greater engagement with and commitment to communicators and their content (Osei-Frimpong & McLean, 2018). In turn, the feeling of social presence makes it less likely that people will check the truth of information (Jun et al., 2017). This is particularly problematic when dealing with extreme right-wing content, e.g. disinformation or conspiracy theories.

EMOTIONALISATION OF CONTENT

In the context of their communication, radicalised communicators talk about fears, uncertainties and developmental tasks; they also use emotionalising content and images to make their content relatable and convince followers of their world view (Frischlich, 2021; Frischlich et al., 2021; Schmitt, Harles, et al., 2020; Schneider et al., 2019). In the so-called post-truth era, emotions, as well as perceived truths, are becoming a key manipulation tool of extreme right-wing creators. An experimental study by Lillie and colleagues (2021) indicates that narrative content which triggers fear among recipients leads to more flow experiences – i.e. the complete absorption of users in the reception of the content – and encourages behavioural intentions; on the other hand, fear reduces the willingness to contradict content. This makes it appear more convincing.

The development of social media into platforms for creating, publishing and interacting with (audio-)visual content supports the communication and effect of this sort of content. In particular, (audio-)visual content is suitable for conveying emotional messages (Houwer & Hermans, 1994) and thus generating corresponding emotional responses. In turn, this affects information processing, as the brain pays more attention to processing the emotional reaction than to the information (Yang et al., 2023). Tritt et al. (2016) found that politically conservative people appear to respond more easily to emotional stimuli than liberals.

The immersive effects outlined so far may result in followers becoming more intensely involved in the world portrayed by creators, forging a deeper emotional bond and identifying more strongly with the content presented (Feng et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2020; Slater & Rouner, 2002; Wunderlich, 2023).

THE ROLE OF PLATFORM FUNCTIONS

Time plays an important role on social media. Users’ attention must be captured quickly in order to attract them to the platform. It is fair to assume that immersive effects of communication on social media are intensified through the design and functional logic of the platforms. Platform-specific algorithms and dark patterns play a special role here.

Algorithms determine relevance and importance

In addition to highlighting the relevance and importance of certain content, algorithms encourage the emotional involvement of users by preferentially showing them content that they or similar users potentially prefer. This is designed to attract users to the platform and content and retain them for as long as possible; it is part of the platforms’ business model. In this way, platforms let users plunge deeper and deeper into the virtual worlds. This makes them an immersive and effective recruitment tool. The algorithmic selection and sorting of particular content depends on various factors including the type of content, its placement, the language used, the degree of networking between those disseminating it and the responses from users (Peters & Puschmann, 2017).

Commercial platforms prioritise posts that trigger emotional reactions, polarise opinions or promote intensive communication between members (Grandinetti & Bruinsma, 2023; Huszár et al., 2022; Morris, 2021). In particular, visual presentation modes such as photos, videos and memes trigger affective emotions and reactions among recipients and draw them in (Maschewski & Nosthoff, 2019). Algorithmic networking provides technical reinforcement of users’ emotional connection and involvement with the content. This also applies to contact with antidemocratic content. Studies suggest that social media algorithms can facilitate the spread of extreme right-wing activities (Whittaker et al., 2021; Yesilada & Lewandowsky, 2022) – sometimes similar keywords are enough, as with unproblematic content (Schmitt et al., 2018). In particular, people who are interested in niche topics (e.g. conspiracy theories) (Ledwich et al., 2022) and who follow platform recommendations for longer (M. A. Brown et al., 2022) are manoeuvred into corresponding filter bubbles by the algorithms. At the same time, however, the majority of users are shown moderate content (M. A. Brown et al., 2022; Ledwich et al., 2022).

In recent years, TikTok has faced scrutiny particularly because of its strong algorithmic control. This makes it even more likely that users will unintentionally come into contact with radicalised content (Weimann & Masri, 2021). In addition, the stream of content continues to run if users do not actively interrupt it, thus creating a much more immersive experience on the platform compared to other social media (Su, Zhou, Gong, et al., 2021; Su, Zhou, Wang, et al., 2021). Sometimes the platform is even said to have addictive potential due to its functions (e.g. Qin et al., 2022). It is difficult to break away from, and this poses a great danger for users, especially given the increase in extremist communication on TikTok.

Dark patterns as mechanisms to enhance immersion

Dark patterns also play a role in discussions around the immersive effect of social media. These describe platforms’ design decisions that use deceptive or manipulative tactics to keep users on the platforms and encourage them to make (uninformed) usage decisions (Gray et al., 2023). On social media, dark patterns are primarily aimed at retaining users’ attention for long periods, ensuring excessive and immersive use of the platforms and getting users to perform actions (e.g. likes). Examples of dark patterns are: activity notifications, the major challenge on Facebook of really logging out of the platform or even deleting an account, or the often counter-intuitive colours of cookie notifications which mean that users accept all of them, including unnecessary ones. Nearly all popular platforms and applications have dark patterns; many users do not notice them (Bongard-Blanchy et al., 2021; Di Geronimo et al., 2020). Creators also aim to influence user behaviour through dark patterns. For example, they manipulate popularity metrics (e.g. likes, number of followers) and images to try to artificially boost their credibility and generate attention for their content (Luo et al., 2022).

WHAT IS AN EFFECTIVE PREVENTIVE RESPONSE?

The immersiveness of extremist social media communication poses a major challenge in terms of preventive measures. This relates in particular to the many different levels that must be considered in this context. In the following, the considerations of prevention measures are specified at a) content level, b) platform level and c) media level. To clearly define the measures from the users’ point of view, we will use the three prevention levels of awareness, reflection and empowerment (Schmitt, Ernst, et al., 2020). Awareness includes a general consideration or a general awareness (e.g. of one’s own usage behaviour, extremist narratives, platform functioning), while reflection refers to critical reflection on content and the functioning of the media. Empowerment, however, means the ability of recipients to position themselves as regards certain media content or functions and be capable of acting.

At content level (a) awareness must be raised about extremist content and its specific digital forms of communication and representation on social media. This is therefore about creating awareness of how right-wing extremist creators communicate in order to gain the attention of social media users, generate interest in their narratives and ultimately motivate people to act in accordance with the far-right world view (Schmitt, Ernst, et al., 2020). Furthermore, users should be enabled to take a critical stance as regards extremist content so they can position themselves accordingly in social discourse. This positioning does not only have to take place in the context of political discussions – the fact of reporting content to the platform itself or to one of the common reporting platforms (e.g. Jugendschutz.net) also indicates a stance. As well as a strong ability to take a critical view of media, it is particularly important here to have historic, intercultural and political knowledge. Tolerance of ambiguity, which enables people to tolerate complex and possibly contradictory information, is also important.

Platform-related prevention measures (b) should enable users to be aware, understand and reflect on algorithmic functional logic (e.g. what am I being shown and why?) and raise awareness of the mechanisms of action of the platform design (e.g. how is content being shown to me? How is that affecting my actions?) (Di Geronimo et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2022; Taylor & Brisini, 2023). For a school context, there is, for example, the second learning package in the CONTRA lesson series (Ernst et al., 2020) which has been explicitly designed to facilitate the ability to criticise media with regard to algorithms.

On the platform side, it is important to create transparency around algorithms. Disclosure of the platform design, such as clarifying the functional logic of the recommendation algorithm, can help people identify dark patterns – and thus also understand the potential spread dynamics of extremist messages and counteract these (Rau et al., 2022). In a social media context, dark patterns have been relatively poorly researched to date (Mildner et al., 2023). In this field, information from research activities is provided, for example, by the Dark Pattern Detection Project, which also enables users to report dark patterns.

Political regulatory measures, such as those in the Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG) and the Digital Services Act (DSA), can also help as regards the disclosure of platform design and require transparency reports to be provided, for example. With a view to potential new virtual media environments – such as the metaverse – it is essential to enforce transparency rules and consider new forms of design. In what circumstances does the virtual interaction take place? How are the digital activity spaces designed? What criteria are used for the visual representation of the actors, e.g. avatars, and how inclusive is their design?

On the media level (c), it is crucial to raise users’ awareness of their own media behaviour and encourage them to reflect on it. Among other things, this involves questions about the time spent using certain applications (e.g. how long have I spent on TikTok today?) and also the type of use[1] (e.g. what content and mechanisms are drawing me in?). Help could be provided by apps that set time limits or send warnings about the usage times of other apps or block them (e.g. StayFree or Forest). The digital wellbeing function, which can measure the usage time of individual apps, is already established in various smartphone brands.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

The statements above illustrate the levels on which the social media communication of far-right creators can have an immersive effect from a social and psychological perspective. This occurs both as a result of the communication styles they choose and also through the platforms themselves. When these are combined, a parallel world is created – a metaverse – that attracts users in a variety of ways and can therefore have an effect.

From a research perspective, a number of unanswered questions arise. For example, TikTok, as an extremely popular platform, should be examined more thoroughly with regard to its immersive potential. The new possibilities offered by AI-based image generation tools also raise questions about the effect and immersiveness of synthetic imagery produced by extremist communicators. The topic of gaming and right-wing extremism has also gained a lot more attention in recent years (e.g. Amadeu Antonio Stiftung, 2022; Schlegel, no date, 2021). Becoming absorbed in virtual worlds is a key motivation for gamers (for an overview see, for example, Cairns et al., 2014). Currently, there are few reliable findings regarding exactly how far-right actors use gaming for their own purposes, what role avatars, 3D worlds and VR play here and what impact this can have in the context of radicalisation processes. However, some initial findings are available on how interactive games and VR can be used for prevention purposes (e.g. Bachen et al., 2015; Dishon & Kafai, 2022). Through a fun and immersive approach, more abstract topics like politics and democracy – including their controversial aspects – can be explored in an engaging and cooperative way. This makes it possible for people to take different points of view and learn and practise interactions that are also relevant in everyday life. Games can also promote knowledge, empathy and critical thinking. This potential should be explored more fully by researchers and those working in prevention. Although we have outlined a selection of considerations for the prevention of immersive extremist communication, those in the field of prevention are asked to address the various facets of immersiveness in greater detail and possibly use comparable mechanisms for their own goals, taking into account Germany’s prohibition on overwhelming students (Überwältigungsverbot) (bpb, 2011; for criticism of the Beutelsbach Consensus see also Widmaier & Zorn, 2016).

REFERENCES

Amadeu Antonio Stiftung. (2022). Unverpixelter Hass—Gaming zwischen Massenphänomen und rechtsextremen Radikalisierungsraum? https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/neue-handreichung-unverpixelter-hass-gaming-zwischen-massenphaenomen-und-rechtsextremen-radikalisierungsraum-81173/

Ayyadi, K. (2021, August 25). Rechte Influencerinnen: Rechtsextreme Inhalte schön verpackt. Belltow-er.News. https://www.belltower.news/rechte-influencerinnen-rechtsextreme-inhalte-schoen-verpackt-120301/

Bachen, C. M., Hernández-Ramos, P. F., Raphael, C., & Waldron, A. (2015). Civic Play and Civic Gaps: Can Life Simulation Games Advance Educational Equity? Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(4), 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1101038

Bongard-Blanchy, K., Rossi, A., Rivas, S., Doublet, S., Koenig, V., & Lenzini, G. (2021). ”I am Definitely Manipulated, Even When I am Aware of it. It’s Ridiculous!”—Dark Patterns from the End-User Perspective. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461778.3462086

bpb. (2011, April 7). Beutelsbacher Konsens. bpb.de. https://www.bpb.de/die-bpb/ueber-uns/auftrag/51310/beutelsbacher-konsens/

Braddock, K. (2020). Narrative Persuasion and Violent Extremism: Foundations and Implications. In J. B. Schmitt, J. Ernst, D. Rieger, & H.-J. Roth (Hrsg.), Propaganda und Prävention: Forschungser-gebnisse, didaktische Ansätze, interdisziplinäre Perspektiven zur pädagogischen Arbeit zu ext-remistischer Internetpropaganda (S. 527–538). Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28538-8_28

Braddock, K., & Dillard, J. P. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83(4), 446–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555

Brown, E., & Cairns, P. (2004). A grounded investigation of game immersion. CHI ’04 Extended Ab-stracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1297–1300. https://doi.org/10.1145/985921.986048

Brown, M. A., Bisbee, J., Lai, A., Bonneau, R., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2022). Echo Chambers, Rabbit Holes, and Algorithmic Bias: How YouTube Recommends Content to Real Users (SSRN Scholar-ly Paper 4114905). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4114905

Cairns, P., Cox, A., & Nordin, A. I. (2014). Immersion in Digital Games: Review of Gaming Experience Research. In Handbook of Digital Games (S. 337–361). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118796443.ch12

Chadwick, A., & Stanyer, J. (2022). Deception as a Bridging Concept in the Study of Disinformation, Misinformation, and Misperceptions: Toward a Holistic Framework. Communication Theory, 32(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab019

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influ-ence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818815684

Curran, N. (2018). Factors of Immersion. In The Wiley Handbook of Human Computer Interaction (S. 239–254). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118976005.ch13

de Bérail, P., Guillon, M., & Bungener, C. (2019). The relations between YouTube addiction, social anxie-ty and parasocial relationships with YouTubers: A moderated-mediation model based on a cognitive-behavioral framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.007

Dede, C. (2009). Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning. Science, 323(5910), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1167311

Di Geronimo, L., Braz, L., Fregnan, E., Palomba, F., & Bacchelli, A. (2020). UI Dark Patterns and Where to Find Them: A Study on Mobile Applications and User Perception. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376600

Dishon, G., & Kafai, Y. B. (2022). Connected civic gaming: Rethinking the role of video games in civic education. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(6), 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1704791

Echtermann, A., Steinberg, A., Diaz, C., Kommerell, C., & Eckert, T. (2020). Kein Filter für Rechts. cor-rectiv.org. https://correctiv.org/top-stories/2020/10/06/kein-filter-fuer-rechts-instagram-rechtsextremismus-frauen-der-rechten-szene/?lang=de

Ernst, J., Schmitt, J. B., Rieger, D., & Roth, H.-J. (2020). #weARE – Drei Lernarrangements zur Förderung von Medienkritikfähigkeit im Umgang mit Online-Propaganda in der Schule. In J. B. Schmitt, J. Ernst, D. Rieger, & H.-J. Roth (Hrsg.), Propaganda und Prävention: Forschungsergebnisse, di-daktische Ansätze, interdisziplinäre Perspektiven zur pädagogischen Arbeit zu extremistischer Internetpropaganda (S. 361–393). Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28538-8_17

Eyal, K., & Dailey, R. M. (2012). Examining Relational Maintenance in Parasocial Relationships. Mass Communication and Society, 15(5), 758–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.616276

Farivar, S., & Wang, F. (2022). Effective influencer marketing: A social identity perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 67, 103026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103026

Feng, Y., Chen, H., & Kong, Q. (2021). An expert with whom i can identify: The role of narratives in in-fluencer marketing. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 972–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1824751

Fielitz, M., & Marcks, H. (2020). Digitaler Faschismus: Die sozialen Medien als Motor des Rechtsext-remismus. Dudenverlag.

Frischlich, L. (2021). #Dark inspiration: Eudaimonic entertainment in extremist Instagram posts. New Media & Society, 23(3), 554–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819899625

Frischlich, L., Hahn, L., & Rieger, D. (2021). The Promises and Pitfalls of Inspirational Media: What do We Know, and Where do We Go from Here? Media and Communication, 9(2), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i2.4271

Grandinetti, J., & Bruinsma, J. (2023). The Affective Algorithms of Conspiracy TikTok. Journal of Broad-casting & Electronic Media, 67(3), 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2022.2140806

Gray, C. M., Sanchez Chamorro, L., Obi, I., & Duane, J.-N. (2023). Mapping the Landscape of Dark Patterns Scholarship: A Systematic Literature Review. Companion Publication of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563703.3596635

Harff, D., Bollen, C., & Schmuck, D. (2022). Responses to Social Media Influencers’ Misinformation about COVID-19: A Pre-Registered Multiple-Exposure Experiment. Media Psychology, 25(6), 831–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2022.2080711

Haywood, N., & Cairns, P. (2006). Engagement with an Interactive Museum Exhibit. In T. McEwan, J. Gulliksen, & D. Benyon (Hrsg.), People and Computers XIX — The Bigger Picture (S. 113–129). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-84628-249-7_8

Houwer, J. D., & Hermans, D. (1994). Differences in the affective processing of words and pictures. Cognition and Emotion, 8(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939408408925

Hu, L., Min, Q., Han, S., & Liu, Z. (2020). Understanding followers’ stickiness to digital influencers: The effect of psychological responses. International Journal of Information Management, 54, 102169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102169

Huszár, F., Ktena, S. I., O’Brien, C., Belli, L., Schlaikjer, A., & Hardt, M. (2022). Algorithmic amplification of politics on Twitter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(1), e2025334119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2025334119

Igartua, J.-J., & Cachón-Ramón, D. (2023). Personal narratives to improve attitudes towards stigma-tized immigrants: A parallel-serial mediation model. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 26(1), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211052511

Jun, Y., Meng, R., & Johar, G. V. (2017). Perceived social presence reduces fact-checking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(23), 5976–5981. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700175114

Jung, N., & Im, S. (2021). The mechanism of social media marketing: Influencer characteristics, con-sumer empathy, immersion, and sponsorship disclosure. International Journal of Advertising, 40(8), 1265–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1991107

Kero, S. (im Druck). Jung, weiblich und extrem rechts. Die narrative Kommunikation weiblicher Akteu-rinnen auf der Plattform Instagram. easy_social sciences.

Kim, J., Kim, J., & Yang, H. (2019). Loneliness and the use of social media to follow celebrities: A mod-erating role of social presence. The Social Science Journal, 56(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.12.007

Kim, J., & Song, H. (2016). Celebrity’s self-disclosure on Twitter and parasocial relationships: A medi-ating role of social presence. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 570–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.083

Ledwich, M., Zaitsev, A., & Laukemper, A. (2022). Radical bubbles on YouTube? Revisiting algorithmic extremism with personalised recommendations. First Monday. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v27i12.12552

Leite, F. P., Pontes, N., & Baptista, P. de P. (2022). Oops, I’ve overshared! When social media influenc-ers’ self-disclosure damage perceptions of source credibility. Computers in Human Behavior, 133, 107274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107274

Lillie, H. M., Jensen, J. D., Pokharel, M., & Upshaw, S. J. (2021). Death Narratives, Negative Emotion, and Counterarguing: Testing Fear, Anger, and Sadness as Mechanisms of Effect. Journal of Health Communication, 26(8), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1981495

Luo, M., Hancock, J. T., & Markowitz, D. M. (2022). Credibility Perceptions and Detection Accuracy of Fake News Headlines on Social Media: Effects of Truth-Bias and Endorsement Cues. Communi-cation Research, 49(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921321

Maschewski, F., & Nosthoff, A.-V. (2019). Netzwerkaffekte. Über Facebook als kybernetische Regie-rungsmaschine und das Verschwinden des Subjekts. In R. Mühlhoff, A. Breljak, & J. Slaby (Hrsg.), Affekt Macht Netz: Auf dem Weg zu einer Sozialtheorie der Digitalen Gesellschaft (1. Aufl., Bd. 22, S. 55–80). transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839444399

Masuda, H., Han, S. H., & Lee, J. (2022). Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in so-cial media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technological Fore-casting and Social Change, 174, 121246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121246

Mildner, T., Savino, G.-L., Doyle, P. R., Cowan, B. R., & Malaka, R. (2023). About Engaging and Govern-ing Strategies: A Thematic Analysis of Dark Patterns in Social Networking Services. Proceed-ings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580695

Morris, L. (2021, Oktober 27). In Poland’s politics, a ‚so- cial civil war‘ brewed as Facebook rewarded online anger. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/10/27/poland-facebook-algorithm/

Moyer-Gusé, E. (2008). Toward a Theory of Entertainment Persuasion: Explaining the Persuasive Effects of Entertainment-Education Messages. Communication Theory, 18(3), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2008.00328.x

mpfs. (2022). JIM-Studie 2022. Jugend, Information, Medien. Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger. https://www.mpfs.de/fileadmin/files/Studien/JIM/2022/JIM_2022_Web_final.pdf

Mühlhoff, R., & Schütz, T. (2019). Die Macht der Immersion. Eine affekttheoretische Perspektive. https://doi.org/10.25969/MEDIAREP/12593

Müller, P. (2022). Extrem rechte Influencer*innen auf Telegram: Normalisierungsstrategien in der Corona-Pandemie. ZRex – Zeitschrift für Rechtsextremismusforschung, 2(1), Art. 1. https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/zrex/article/view/39600

Munger, K., & Phillips, J. (2022). Right-Wing YouTube: A Supply and Demand Perspective. The Interna-tional Journal of Press/Politics, 27(1), 186–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220964767

Murray, J. H. (1998). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. The MIT Press.

Nilsson, N. Chr., Nordahl, R., & Serafin, S. (2016). Immersion revisited: A review of existing definitions of immersion and their relation to different theories of presence. Human Technology, 12(2), 108–134.

Osei-Frimpong, K., & McLean, G. (2018). Examining online social brand engagement: A social presence theory perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 128, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.10.010

Peters, I., & Puschmann, C. (2017). Informationsverbreitung in sozialen Medien. In J.-H. Schmidt & M. Taddicken (Hrsg.), Handbuch soziale Medien (S. 211–232). Springer VS.

pre:bunk. (2023). Rechtsextremismus und TikTok, Teil 1: Von Hatefluencer*innen über AfD und bis rechter Terror. Belltower.News. https://www.belltower.news/rechtsextremismus-und-tiktok-teil-1-147835/

Qin, Y., Omar, B., & Musetti, A. (2022). The addiction behavior of short-form video app TikTok: The information quality and system quality perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.932805

Rau, J., Kero, S., Hofmann, V., Dinar, C., & Heldt, A. P. (2022). Rechtsextreme Online-Kommunikation in Krisenzeiten: Herausforderungen und Interventionsmöglichkeiten aus Sicht der Rechtsextre-mismus- und Platform-Governance-Forschung. Arbeitspapiere des Hans-Bredow-Instituts. https://doi.org/10.21241/SSOAR.78072

Rösch, V. (2023). Heimatromantik und rechter Lifestyle. Die rechte Influencerin zwischen Self-Branding und ideologischem Traditionalismus. GENDER – Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesell-schaft, 15(2), Art. 2. https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/gender/article/view/41966

Schlegel, L. (o. J.). Super Mario Brothers Extreme. Gaming und Rechtsextremismus. Abgerufen 9. Sep-tember 2023, von https://gaming-rechtsextremismus.de/themen/super-mario-brothers-extreme/

Schlegel, L. (2021). The Role of Gamification in Radicalization Processes. modus | zad. https://modus-zad.de/publikation/report/working-paper-1-2021-the-role-of-gamification-in-radicalization-processes/

Schmitt, J. B., Ernst, J., Rieger, D., & Roth, H.-J. (2020). Die Förderung von Medienkritikfähigkeit zur Prävention der Wirkung extremistischer Online-Propaganda. In J. B. Schmitt, J. Ernst, D. Rieger, & H.-J. Roth (Hrsg.), Propaganda und Prävention: Forschungsergebnisse, didaktische Ansätze, interdisziplinäre Perspektiven zur pädagogischen Arbeit zu extremistischer Internetpropagan-da (S. 29–44). Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28538-8_2

Schmitt, J. B., Harles, D., & Rieger, D. (2020). Themen, Motive und Mainstreaming in rechtsextremen Online-Memes. Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 68(1–2), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634X-2020-1-2-73

Schmitt, J. B., Rieger, D., Rutkowski, O., & Ernst, J. (2018). Counter-messages as Prevention or Promoti-on of Extremism?! The Potential Role of YouTube Recommendation Algorithms. Journal of Communication, 68(4), 780–808. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy029

Schneider, J., Schmitt, J. B., Ernst, J., & Rieger, D. (2019). Verschwörungstheorien und Kriminalitäts-furcht in rechtsextremen und islamistischen YouTube-Videos. Praxis der Rechtspsychologie, 1, Art. 1.

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in adverti-sing: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

Schwarz, K. (2020). Hasskrieger: Der neue globale Rechtsextremismus. Herder.

Silva, D. E., Chen, C., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Facets of algorithmic literacy: Information, experience, and indi-vidual factors predict attitudes toward algorithmic systems. New Media & Society, 14614448221098042. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221098042

Slater, M. D., & Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment—Education and Elaboration Likelihood: Under-standing the Processing of Narrative Persuasion. Communication Theory, 12(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Strick, S. (2021). Rechte Gefühle: Affekte und Strategien des digitalen Faschismus. Transcript.

Su, C., Zhou, H., Gong, L., Teng, B., Geng, F., & Hu, Y. (2021). Viewing personalized video clips recom-mended by TikTok activates default mode network and ventral tegmental area. NeuroImage, 237, 118136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118136

Su, C., Zhou, H., Wang, C., Geng, F., & Hu, Y. (2021). Individualized video recommendation modulates functional connectivity between large scale networks. Human Brain Mapping, 42(16), 5288–5299. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25616

Taylor, S. H., & Brisini, K. S. C. (2023). Parenting the Tiktok Algorithm: An Algorithm Awareness as Pro-cess Approach to Online Risks and Opportunities for Teens on Tiktok (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4446575). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4446575

Tritt, S. M., Peterson, J. B., Page-Gould, E., & Inzlicht, M. (2016). Ideological reactivity: Political conser-vatism and brain responsivity to emotional and neutral stimuli. Emotion, 16(8), 1172–1185. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000150

Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2021). TikTok’s Spiral of Antisemitism. Journalism and Media, 2(4), Art. 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040041

Whittaker, J., Looney, S.-0007-3114-0806, Reed, A., & Votta, F. (2021). Recommender systems and the amplification of extremist content. https://doi.org/10.14763/2021.2.1565

Widmaier, B., & Zorn, P. (Hrsg.). (2016). Brauchen wir den Beutelsbacher Konsens? Eine Debatte der politischen Bildung. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. https://www.lpb-mv.de/nc/publikationen/detail/brauchen-wir-den-beutelsbacher-konsens-eine-debatte-der-politischen-bildung/

Wunderlich, L. (2023). Parasoziale Meinungsführer? Eine qualitative Untersuchung zur Rolle von Social Media Influencer*innen im Informationsverhalten und in Meinungsbildungsprozessen junger Menschen. Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft, 71(1–2), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634X-2023-1-2-37

Yang, Y., Xiu, L., Chen, X., & Yu, G. (2023). Do emotions conquer facts? A CCME model for the impact of emotional information on implicit attitudes in the post-truth era. Humanities and Social Sci-ences Communications, 10(1), Art. 1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01861-1

Yesilada, M., & Lewandowsky, S. (2022). Systematic review: YouTube recommendations and proble-matic content. Internet policy review, 11(1), 1652. https://doi.org/10.14763/2022.1.1652

Zimmermann, D., Noll, C., Gräßer, L., Hugger, K.-U., Braun, L. M., Nowak, T., & Kaspar, K. (2022). In-fluencers on YouTube: A quantitative study on young people’s use and perception of videos about political and societal topics. Current Psychology, 41(10), 6808–6824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01164-7

[1] Tools such as Dataskop can show TikTok use.